Schtschedrin, Rodion: Parade à la russe

2005, 2006

2006

Rodion Schtschedrin

Dmitry Sitkovetsky

David Geringas

Jascha Nemtsov

Rodion Schtschedrin

Tr. 1 Rodion Schtschedrin: Piano Terzetto

Tr. 3 Rodion Schtschedrin: Conversation – Rubato recitando

Tr. 4 Rodion Schtschedrin: Let's Play an Opera by Rossini – Recitative - Allegro assai

Tr. 5 Rodion Schtschedrin: Humoreske – Sostenuto assai

Tr. 6 Rodion Schtschedrin: Sonata for Violoncello and Piano

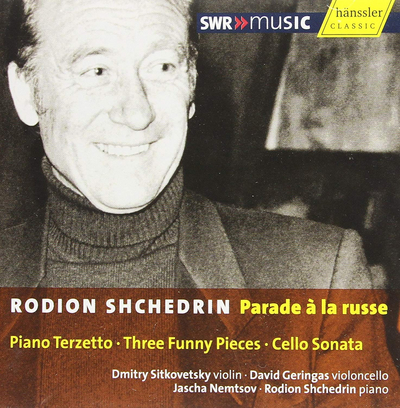

The door opens and he is already standing in the middle of the recording studio: one of the most important Russian composers, honorary professor at the Moscow and St. Petersburg Conservatories, winner of the highest national and international distinctions, chairman of many years’ standing of the Russian Composers’ Association (and in that capacity the direct successor and favored candidate of Dmitry Shostakovich) – Rodion Shchedrin. He has such a lively, youthful manner that his age is hardly noticeable. His attentive, friendly gaze conveys sincere interest for his interlocutor. He sits down with his sheet music next to us – his praise is honest and encouraging, his criticism objective and enriching. For us, the recording session turns into an encounter with a great musician and an amiable human being.

“Inner Freedom”

“People must always rely on their inner freedom. The freedom that no one gives you, that you must create out of your own self! No matter what political system you’re in, if you do not have this freedom, you are not an artist.” These words, spoken by Shchedrin in an interview, are not an empty declaration, but the most important principle of his life and work. Since 1992, he has been dividing his time between various countries, living alternately in Moscow, Munich and Lithuania, and feels his connection to Germany primarily in his work together with Schott publishers in Mainz. In contrast to other musicians, who presented themselves as persecuted dissidents as soon as they arrived in the West, Shchedrin never tried to capitalize on the circumstances of his life for political reasons. Yet he was at the time the only musician who refused to give his signed approval to the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Soviet troops in 1968. Not coincidentally, he then took an active part in the reform movement as a member of parliament during the Gorbachev era. However, such facts are not what has made his works known around the world, but solely the quality of his music, which attracts such performers as Lorin Maazel, Mstislav Rostropovich, Mariss Jansons, Maxim Vengerov and many others.

Shchedrin proves to be just as uncompromising when it comes to the fashionable avant-garde currents in the Western music business. “I have never committed myself to one of these minor musical religions,” he says outspokenly, and continues his criticism of the “dictatorship of the avant-garde”: “If you go to the premiere of an ‘avant-garde work’, you know perfectly well what you can expect. Neither melody nor rhythm, because it is ‘embarrassing’ to write like that. And why should you go at all, when there is no mystery left? This is how modern music lost its audience, isolating itself in small festival ghettos.” Even though Shchedrin has actively looked into new techniques of composition in great depth, his own artistic individuality (which he refers to as “intuition”) always remains the most important thing for him. Inner freedom is thus of existential significance to him from an esthetic point of view, as well.

It is above all Russian musical culture in the widest sense that influenced Shchedrin’s esthetics and his musical idiom. “Russia means incredibly much to me ... I am simply a son of Russia – and I never want to cut myself off from these roots,” he admits, and vigorously protests if he is referred to as an emigrant. And indeed, the composer’s vital bond with Russia, its traditions and its language, has never broken off. Having grown up in a musical family, Shchedrin studied at the Moscow Conservatory, a school steeped in tradition, and absorbed many influences from folk music culture along with his professional training, from peasant folklore up to circus music. Particularly important to him was the choir music of the Russian Orthodox church, familiar to him since earliest childhood from the religious atmosphere of his parents’ home.

“At the moment, I am mainly happy“

When asked about the circumstances of his creative work, Shchedrin invokes Shostakovich, who used to say, “You can compose in a doghouse as long as you have ideas in your head.” “Composing is like love”, Shchedrin adds, “No matter how bad you may feel, no matter how many worries you may have, when you fall in love, everything else recedes into the background, only the object of your love exists.” However, the fact cannot be overlooked that this composer has enjoyed an extremely productive period since the beginning of the 1990’s, when he was able to separate himself from everyday life in Moscow.

This CD presents three chamber music compositions, all of which were composed in the mid- 1990’s and represent various contrasting facets of Shchedrin’s work. The Piano Terzetto of 1995 was commissioned by the “L’Association Parade” in Paris, The two movements of this trio bear programmatic titles. According to the composer, the first movement, Luncheon on the Grass, transforms “into musical terms, so to speak, a lyric subject which has already become a classic in painting”. If this makes us think of the well-known painting by Édouard Manet of a naked woman in the company of two welldressed gentlemen, then the composer’s allusion at first seems rather puzzling. However, if we consider what the picture imparts beneath the surface – sensuality, liberated from the conventions of society and breaking out of a classicist, pastoral framework – then Shchedrin’s idea is more comprehensible. In his music, as well, classicist allusions and prim sounds cannot cover up the hidden passion. In contrast to Manet’s painting, whose ironical note can hardly be overlooked, Shchedrin’s Luncheon on the Grass is, however, marked rather by a slightly melancholy, nostalgic mood.

The idea behind the program of the second movement, Parade alla russe, is more obvious. Beholden to the sponsor, this music at once relates to the famous “Parade” by Eric Satie, as well as the esthetics of his librettist, Jean Cocteau, with musical ideals of sharpness, coolness and mechanical hardness. However, Shchedrin’s musical grotesque is Russian through and through. As he did a few years before in his Concerto for Orchestra No. 3, “Old Russian Circus Music”, he here quotes a song that is even supposed to be sung by the instrumentalists. While in the concerto for orchestra it was the famous Ochi Chornye, or “Black Eyes”, the high point of the piano trio is the old Russian soldier’s song “Nightingale, little bird”. All three musicians sing it at the top of their voices, bellowing against a background of deafeningly loud, dissonant chords. Then events are again immersed a nostalgic flair.

The Sonata for Violoncello and Piano, written one year after the trio, premiered in 1997, played by the composer and Mstislav Rostropovich. In contrast to the trio, this sonata contains no programmatic clues. The conception of this monumental three-movement cycle is unusual. The first, slow movement recalls late Shostakovich in its rigor and concentration, which borders on asceticism. The second movement is a kind of distorted serenade, although the sensual pathos of the cello melody stands in odd contrast to the mechanistic-unemotional accompanying figures and is “canceled out” by these, in a manner of speaking. The finale, which again is slow, starts with a somber “de profundis” on both instruments. In the middle section, the lyric melody intensifies from dolcissimo up to the utmost emotional tension, finally breaking down when the first theme returns. The hard, implacable sounds of the final episode seem to take away the last hope.

Another remarkable aspect of Shchedrin – his musical humor – is embodied in the Three Funny Pieces of 1997. Here the composer arranges three of his earlier solo piano pieces for piano trio – the famous Humoresque (1957), as well as two pieces from the “Notebook for Youth” of 1981: Conversation (a rhythmically and metrically unfettered imitation of living intonations of spoken language) and Let’s Play an Opera by Rossini (a perfect copy of this composer’s style without any trace of quotation).

In a recent interview, Shchedrin spontaneously said, “At the moment, I am mainly happy”. For us, his performers, it remains to hope that this will inspire him to write many more masterful works and that he will not have to compose them in a doghouse.

Jascha Nemtsov