Schostakowitsch, Dmitrij

Artikelinfo

2006, 2005

2005

Dimitri Schostakowitsch

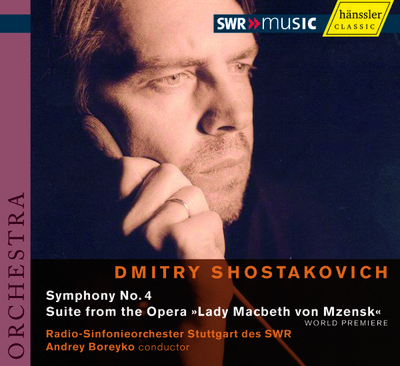

Radio-Sinfonieorchester Stuttgart des SWR

Andrey Boreyko

Tr. 1 Dimitri Schostakowitsch: Symphony No. 4 c minor op. 43

Tr. 4 Dimitri Schostakowitsch: Suite op. 29a (from: Lady Macbeth von Mzensk)

DMITRY SHOSTAKOVICH (1906–1975)

Symphony No. 4 in C Minor, Op. 43 (1935–36)

Dmitry Shostakovich was prompted to write his Symphony No. 4 in C Minor, Op. 43 primarily by his friendship with the cultural philosopher and musicologist Ivan Sollertinsky, whom he got to know in 1927 and who published the first Russian book on Gustav Mahler in 1932. The Fourth Symphony, written in 1935–36, presents something like a synthesis of the tendencies of the early Russian avant-garde on the one hand and the specific idiom and formal ideas of Gustav Mahler on the other – an entirely new direction for Shostakovich.

This artistic idea first came to fruition independently of the political environment of the early 1930’s. But in the middle of work, the notorious article “Chaos Instead of Music” broke in Pravda on January 28, 1936, a merciless settling of accounts with his alleged “tendencies hostile to the people”, especially in Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk. The demand for “popular appeal” and “comprehensibility” posited by “Socialist Realism” was now the doctrine of the state’s official cultural policy. Although Shostakovich finished composing the symphony, he decided to withdraw it during the final rehearsal after consulting with his close friends, particularly since he was not at all satisfied with the work of the conductor, the German emigrant Fritz Stiedry.

The Fourth Symphony was left to gather dust in a drawer; the distinctly milder and more “popular” style of his Fifth, which soon followed, at least enabled Shostakovich’s work to be tolerated. The manuscript of the Fourth was burned during the siege of Leningrad in the Second World War; Shostakovich reconstructed the work later on the basis of the particella and the parts written out. Not until December 30, 1961, did a political thaw enable the symphony to premiere at long last. It was an overwhelming success for the composer, even though the roughly 65-minute work makes enormous demands on the musicians as well as the audience.

This problem child among Shostakovich’s symphonies, not performed until so long after its nativity, today is nonetheless held to be his symphonic masterpiece, looking back over his oeuvre as a whole. The formal structure of this work scored for a gigantic orchestra is already extraordinarily original. Two colossal outer movements, each lasting nearly half an hour, frame a brief, intermezzo-like movement: first a movement in extended sonata form, then a droll scherzo and in third place a final movement of varied symphonic character introduced by a funeral march. While the funeral march is the most conspicuous link to Mahler, the triumphal march at the end is the epitome of an anti-apotheosis, roaring as if in torture only to collapse at its climax and let the symphony die away with a sustained C Minor chord – anticipating the oppressive events of the decades to come and yet a symphonic picture of awesome, incisive power.

Hartmut Lück

Suite op. 29 a from the Opera » Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk«

Dmitry Shostakovich‘s early international fame of was due particularly to his opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, whose premiere in 1934 was a smashing success. However, the work’s march of triumph came to an abrupt end when on January 28, 1936, it became the subject of a devastating article in Pravda, presumably initiated by Stalin himself. Following this, Shostakovich found himself isolated in society and in the composers’ association, and branded as an enemy of the people of the USSR until his temporary rehabilitation. At the center of the opera is the fate of Katerina Ismailova, who suffers from loneliness and boredom in her unhappy, childless marriage to a wealthy merchant. When her husband goes away for a long period, she gets involved in an affair with Sergei, the hired man. When her father- in-law discovers their liaison, she kills him. Her suspicious husband also falls victim to this lethal passion. The murder is finally discovered at Katerina’s and Sergei’s wedding celebration and both are arrested. When Sergei turns his attentions to another woman on the way to Siberia, the distraught Katerina jumps into a lake and drowns, taking her rival with her.

Elements of tragedy and satire enter into a carefully calculated union. Musically, this appears in the form of contrasts between highly dramatic scenes and banal music, all based on a largely alien tonality. Shostakovich makes use of these polystylistic contrasts to musically steer the empathy entirely onto the figure of Katerina and to make all those around her look ridiculous by means of emphatic, grotesque parody. “I have tried to create an opera which is a revealing satire, which pulls down masks and will make people hate all the horrific despotism and snide behavior of tyrannical Russian merchants.”

Shostakovich’s main concern was to emphasize again and again the extraordinary significance of the symphonic roots of all his opera and stage compositions. This is also affirmed by the weight given to the orchestral interludes, which help to merge the nine scenes of the opera into a uniform whole. In these interludes, he uses orchestration to advance the plot and create points of culmination full of tension. “Musical interludes,” wrote Shostakovich in an article for the Moscow premiere in 1934, “are nothing other than the continuation and development of the preceding musical idea, and play an enormous part in depicting the events on stage. In this sense, the enormous part played by the orchestra grows, it no longer accompanies, but plays a role of its own which is at least as important, or perhaps even more important, than the soloists and the chorus.” Shostakovich arranged the Suite op. 29 a, consisting of three interludes, shortly after completing the opera. It can be assumed that the dramatic fate of the opera also had an effect on the history of the Suite’s performance, so that it, too, was not played for at least another twenty years.

Anke Sonnek